During my minor Service Design, I worked on a challenging and innovative project focused on improving hygiene within shared mobility in the Amsterdam region, commissioned by Vervoerregio Amsterdam (a regional public transport authority responsible for public transport concessions, infrastructure, and mobility planning across 14 municipalities). This project, with my final concept called CleanRide, aims to increase user-friendliness and build trust among users of shared scooters and cars through smart technology and practical tools. The solution takes the form of an extension to the existing apps of shared mobility providers (such as Felyx), designed specifically to improve hygiene standards in shared mobility.

Throughout this project, I conducted extensive research into the current pain points and needs of shared mobility users. Through interviews, user trips, and desk research, I gathered valuable insights that contributed to the development of a Customer Journey Map, a Need‑Based Profile, a Stakeholder Map, and, last but not least, a detailed Program of Requirements (PoR or PvE in Dutch). This PoR/PvE, which I prioritized using the MoSCoW method, served as the foundation for the solutions I designed — including the integration of hygiene kits in vehicles and a mobile app that tracks cleaning status and rewards users for leaving used vehicles clean. In addition, I applied several Creative Research methods, such as a concept map (or 'Denkkaart' in Dutch), solution visualization, card sorting, interviewing with a mind map, a morphological chart, and a future scenario/vision for beyond 2035.

Design Challenge

The design challenge for this project was formulated as follows: "What should Vervoerregio Amsterdam (VRA) take into account regarding the user in relation to shared mobility in the region, with an emphasis on improving hygiene, while at the same time maintaining livability, so that the threshold for using shared mobility can be lowered for the target group?" (originally defined in Dutch).

The design challenge for this project was formulated as follows: "What should Vervoerregio Amsterdam (VRA) take into account regarding the user in relation to shared mobility in the region, with an emphasis on improving hygiene, while at the same time maintaining livability, so that the threshold for using shared mobility can be lowered for the target group?" (originally defined in Dutch).

Program of Requirements (PoR, or 'PvE' in Dutch)

Based on the desk research, interviews, user trips, Customer Journey Mapping, a Need‑Based Profile, meetings with all the stakeholders, and a Feedback Frenzy (interim presentation) with the client, Vervoerregio Amsterdam (VRA), I drafted the following Program of Requirements (PoR/PvE) and subsequently prioritized it using the MoSCoW method:

Based on the desk research, interviews, user trips, Customer Journey Mapping, a Need‑Based Profile, meetings with all the stakeholders, and a Feedback Frenzy (interim presentation) with the client, Vervoerregio Amsterdam (VRA), I drafted the following Program of Requirements (PoR/PvE) and subsequently prioritized it using the MoSCoW method:

Ideation ('Ideegeneratie' in Dutch)

For the Ideation phase, I chose to integrate various technologies and solutions that addressed the design challenge of improving hygiene in shared mobility within the Amsterdam region. In this process, I applied methods such as the ‘Crazy 8’ technique and developed a future vision for beyond 2035.

For the Ideation phase, I chose to integrate various technologies and solutions that addressed the design challenge of improving hygiene in shared mobility within the Amsterdam region. In this process, I applied methods such as the ‘Crazy 8’ technique and developed a future vision for beyond 2035.

Crazy 8: Shown above are six concepts I developed for the Feedback Frenzy (an interim presentation), to give the client, Vervoerregio Amsterdam (VRA), an early idea of the solutions I had in mind.

Beyond 2035: Future Vision

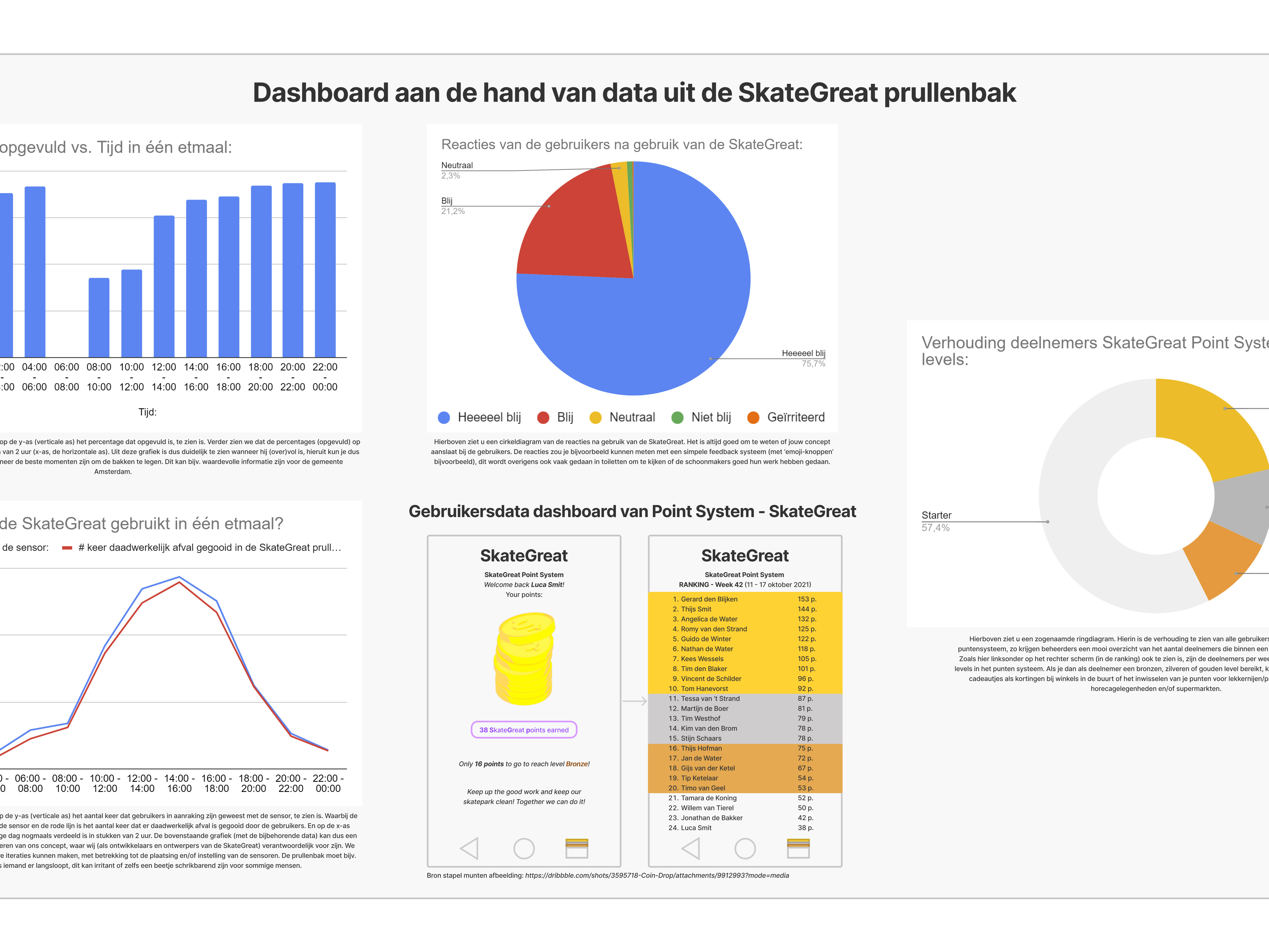

Based on my research and experience (observation rounds and user trips), I found that an improved mobile application can be a crucial element in enhancing the user experience and ensuring hygiene.

This app will include a comprehensive onboarding process, with clear instructions and warnings regarding first‑time use as well as keeping (and leaving) the shared vehicle clean (hygiene!).

In addition, I proposed developing a physical prototype. The idea I came up with during the final Ideation sessions was a (mobile) car wash/cleaning hub for shared vehicles, enabling users to easily clean and maintain the vehicle after use. This not only contributes to better hygiene, but also simplifies the cleaning process for the staff of shared mobility providers (such as Felyx). In this way, the hygiene of shared vehicles can be better safeguarded and maintained.

Smart artificial intelligence (AI) could also play a major role in detecting ‘dirty’ vehicles (for example, based on user feedback in the app) and identifying their location, so that staff do not have to check every shared vehicle unnecessarily. This makes the cleaning process more efficient. In addition, a points system could be implemented, rewarding users who consistently leave their vehicles clean with benefits such as discounts on their next ride or monthly subscription.

I also found it interesting to explore how such a mobile cleaning hub would be designed and look in practice.

Based on my research and experience (observation rounds and user trips), I found that an improved mobile application can be a crucial element in enhancing the user experience and ensuring hygiene.

This app will include a comprehensive onboarding process, with clear instructions and warnings regarding first‑time use as well as keeping (and leaving) the shared vehicle clean (hygiene!).

In addition, I proposed developing a physical prototype. The idea I came up with during the final Ideation sessions was a (mobile) car wash/cleaning hub for shared vehicles, enabling users to easily clean and maintain the vehicle after use. This not only contributes to better hygiene, but also simplifies the cleaning process for the staff of shared mobility providers (such as Felyx). In this way, the hygiene of shared vehicles can be better safeguarded and maintained.

Smart artificial intelligence (AI) could also play a major role in detecting ‘dirty’ vehicles (for example, based on user feedback in the app) and identifying their location, so that staff do not have to check every shared vehicle unnecessarily. This makes the cleaning process more efficient. In addition, a points system could be implemented, rewarding users who consistently leave their vehicles clean with benefits such as discounts on their next ride or monthly subscription.

I also found it interesting to explore how such a mobile cleaning hub would be designed and look in practice.

Shown above is a model I created during the final Ideation/Creative Research class with Michel Alders. In this exercise, I built the previously described idea using Lego, keeping my future vision for beyond 2035 in mind — which was the assignment for that session.

Finally, I also developed a smaller, short‑term solution: providing hygiene kits in the trunk of shared scooters or in the glove compartment of shared cars. These kits contained essential cleaning products and contributed to improved hygiene for users. Hygiene was mainly a significant issue with shared scooters and cars, and less so with shared bicycles. However, for cargo bikes, one could also question whether the boxes remain clean, as they are often used by teenagers, etc.

In short, the ‘hygiene kit idea’ was also very interesting to elaborate on. Based on input from Michel and the Feedback Frenzy, I was able to formulate the following questions for further exploration in my project:

- What exactly should be included in the hygiene kits?

- What should a hygiene kit look like?

- How large should the kit be?

- Where should users dispose of dirty wipes/wet wipes?

- Is it ethically responsible to provide these kits?

- What would the cost structure look like for purchasing/implementing the hygiene kits?

In conclusion, with this idea I could further elaborate on the composition, size, and ethical aspects of the kits to ensure they would work effectively and responsibly within the shared mobility service.

Creative Research methods

Concept map (Denkkaart in Dutch): The purpose of this concept map is to create a visual overview that helps in understanding the central problem and identifying relevant influences (the forces and factors behind the problem).

Solution visualization: Hygiene‑kit concept visualized partly through sketches (the kit itself and the user interface of the accompanying app) and partly created with Generative AI in Adobe Photoshop (mainly the scooters).

I was able to conduct Card Sorting with five participants (two of them are shown above), all of whom belonged to the target group. Coincidentally, each participant also had a germophobia (or 'smetvrees' in Dutch), which made this research particularly valuable. For this Card Sorting exercise, I created a form in which participants could select and prioritize the products they would want to see included in the hygiene kit. I then asked them to create a top‑8 list, ranking the items from most to least important. I also asked them to explain why they chose those specific products and that particular order. Finally, I asked when they would use/open the hygiene kit and again: Why? The participants enjoyed this research activity, which allowed me to gather useful and insightful answers.

Interviewing with a mind map

I was able to carry out this method with three shared‑mobility users who fit within my Need‑Based Profile: the frugal, hygiene‑conscious bon vivant (preferably with a germophobia, or 'smetvrees' in Dutch).

I was able to carry out this method with three shared‑mobility users who fit within my Need‑Based Profile: the frugal, hygiene‑conscious bon vivant (preferably with a germophobia, or 'smetvrees' in Dutch).

The problem involved the presence of dirt and pathogens on shared vehicles, such as scooters, which were not cleaned regularly or thoroughly. However, I first wanted to clarify what the concept of ‘dirty/unclean’ actually meant for the target group. How did they define ‘dirty/unclean’? And where did they draw the line between ‘dirty’ and ‘clean’? According to the target group, when was something considered dirty and when clean?

The method essentially consisted of interviewing the target group as is often done, but in this case the participants were more active than in a ‘normal’ interview. Based on the questions and topics I had prepared, a detailed mind map emerged during the interview, in which the participants answered my questions. This resulted in very interesting insights.

This problem occurred in both urban and non‑urban/suburban areas where shared mobility is used. In this case, the focus was placed on the Amsterdam region, specifically on Hoofddorp and its surroundings (the municipality of Haarlemmermeer). In fact, this method could be carried out with a group of participants almost anywhere. Because the method was quite active for the participants, it made sense to sit together at a table (arranged in advance), with pens and a large sheet of paper. This way, everyone could easily contribute and write things down, ensuring that as many insights as possible were gathered from each participant.

The problem often became visible during peak usage times, such as rush hours, events, or seasonal peaks when the frequency of use increased. Finally, I believed this method could be applied both at the beginning and midway through the project, in order to gain closer insight into the wishes and mindset of the target group.

This problem occurred in both urban and non‑urban/suburban areas where shared mobility is used. In this case, the focus was placed on the Amsterdam region, specifically on Hoofddorp and its surroundings (the municipality of Haarlemmermeer). In fact, this method could be carried out with a group of participants almost anywhere. Because the method was quite active for the participants, it made sense to sit together at a table (arranged in advance), with pens and a large sheet of paper. This way, everyone could easily contribute and write things down, ensuring that as many insights as possible were gathered from each participant.

The problem often became visible during peak usage times, such as rush hours, events, or seasonal peaks when the frequency of use increased. Finally, I believed this method could be applied both at the beginning and midway through the project, in order to gain closer insight into the wishes and mindset of the target group.

This is important because it can affect the health of users and reduce their willingness to use shared vehicles, which undermines the objectives of the client (Vervoerregio Amsterdam, VRA).

This method was therefore particularly useful for obtaining a clear and complete picture of the respondents’ perspectives on the subject of the research.

This method was therefore particularly useful for obtaining a clear and complete picture of the respondents’ perspectives on the subject of the research.

Shown below is the result of the mind map that emerged from the interview with three participants from my target group:

This CleanRide project emphasized the need for innovation and collaboration between different stakeholders to realize a sustainable and accessible (shared) mobility future. The solutions were presented to the client Vervoerregio Amsterdam (VRA), where the strong visual support and intuitive functionalities of the app and the hygiene kits were positively received.

Morphological chart

By creating a morphological chart, I was able to design, sketch, and develop various (partial) solutions based on the functions I had defined. From these, I could then map out the ‘ideal route,’ which resulted in a potential final solution for the concept, as shown below in two parts.

By creating a morphological chart, I was able to design, sketch, and develop various (partial) solutions based on the functions I had defined. From these, I could then map out the ‘ideal route,’ which resulted in a potential final solution for the concept, as shown below in two parts.

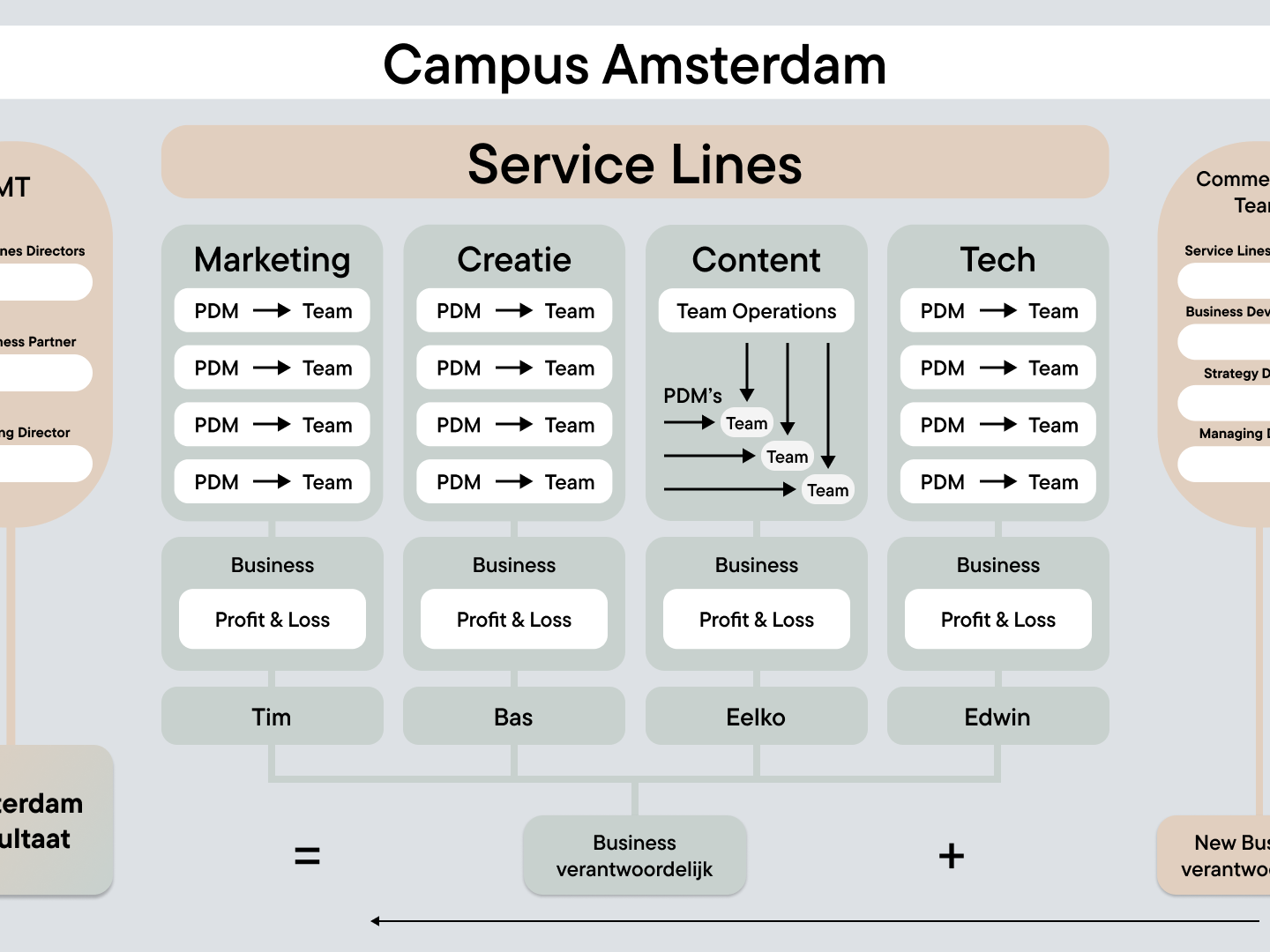

Content Operations

When CleanRide would be put into operation, the focus on Content Operations would be crucial. It would need to be determined which content was already available and which was not. The RACI model would help clarify the responsibilities of each team member and stakeholder. Additional stakeholders would have to be identified and involved to ensure that both static design and dynamic content would be effectively integrated to optimize the user experience.

Content Audit

Available content:

Available content:

- Which content is already available?

The content that might already be available could consist of user manuals, cleaning instructions, FAQs on hygiene practices, and user feedback on the current state of hygiene in shared vehicles.

- Where is this content available?

This content could be available on the shared‑mobility provider’s website, in their mobile app, in brochures, or in the vehicles themselves.

- How (and in what form) is the content made available?

It is likely available in textual form, possibly with supporting images or videos demonstrating the cleaning procedures.

- What must be done to incorporate it into my solution?

To incorporate this content into my solution, we must ensure that it is up to date, easily accessible, and understandable for all users. This may mean revising, translating, or redesigning the content to integrate it into the app or the vehicle.

Not (yet) available content:

- Where does the knowledge about the content reside?

Knowledge about content yet to be created may come from hygiene experts, user feedback, and industry best practices.

- How can the content be created?

The content can be created through collaboration with experts to gather accurate and valuable insights, and with designers and writers to produce the content.

- Who can or should be responsible for that?

A multidisciplinary team consisting of product managers, content creators, UX/UI designers, and hygiene specialists should be responsible for creating the content.

- What resources are needed to create the content?

Resources may include a budget for research and development, access to expertise, and tools for content creation and management.

- What needs to be done to incorporate it into my solution?

A content strategy must be developed that defines how the new content will be integrated into existing platforms and how it will be maintained and updated. This may involve setting up or adapting a content management system (CMS) and implementing processes for regular reviews and updates.

RACI Model

The RACI model, which stands for Responsible, Accountable, Consulted, and Informed, is also seen as the ‘human side’ of Content Operations.

The RACI model, which stands for Responsible, Accountable, Consulted, and Informed, is also seen as the ‘human side’ of Content Operations.

The RACI model contains a chart listing everyone involved in the project along with their role and responsibility, indicated in the chart as: Responsible (or 'verantwoordelijk' in Dutch) (R), Accountable (or 'eindverantwoordelijke' in Dutch) (A), Consulted (or 'geraadpleegd' in Dutch) (C), or Informed (or 'geïnformeerd' in Dutch) (I). (As shown below.)

Additional stakeholders

Additional stakeholders (or 'Extra stakeholders' in Dutch): The extra stakeholders, highlighted in purple, are essential for sustaining Content Operations.

Static Design vs. Dynamic Content

Static design (or 'Statisch' in Dutch) is shown in red, and dynamic content (or 'Dynamisch' in Dutch) is shown in blue.

Service Blueprint (SB)

The Service Blueprint (SB), like a Customer Journey Map, is also a chronological map, but a Service Blueprint (SB) describes more about how the system works/operates. So, in addition to the front stage, the focus is placed on the back stage of a service — for example: 'What happens with the data?' — with less focus on the user experience itself.

Storyboard of my service/concept "CleanRide"

- Scene 1: The user is sitting on the couch watching TV when he sees a commercial for CleanRide — the new add‑on concept for existing shared‑mobility providers, focused on keeping shared vehicles clean. This immediately appeals to him: he’s about to go to a party with his friends, and since he has a germophobia, this feature feels tailor‑made for him. The commercial triggers/prompts him to download the provider’s accompanying app.

- Scene 2: The user searches for the nearest scooter or (shared mobility) hub on the interactive map and reserves a scooter that is available (and clean!). In the app, he immediately sees a notification that the scooter was recently cleaned by the previous user, which reassures him. He follows the walking route in the app to the hub, where the scooter is waiting and lights up as soon as he approaches. This way, he instantly knows which scooter he has reserved.

- Scene 3: The user arrives at the hub, sees the scooter, and checks its cleaning status in the app. He opens the hygiene kit attached to the scooter, takes a wet wipe, and quickly wipes down the handlebar and seat for extra reassurance. He also gives his helmet a quick spray with the deodorizing (and sanitizing) spray, since it smells a bit sweaty. He notices the spray is almost empty and reports this in the app. Now that everything is clean, he feels comfortable using the scooter.

- Scene 4: On his way to the party, the user enjoys the ride. He receives a notification from the app on his phone — a friendly reminder to take a photo after using the scooter as proof that he left it clean. This reinforces his sense of responsibility and contributes to keeping the shared vehicles clean collectively.

- Scene 5: The user arrives at his destination and parks the scooter at the nearest parking hub. He opens the app, takes a photo or video of the clean scooter, and uploads it as proof. He then receives positive feedback and points for contributing to keeping the vehicle clean. These points can later be redeemed for discounts or rewards.

- Scene 6: After the party, the user opens the app again to find a clean, available scooter for the ride home. The app shows that all available scooters have recently been checked and cleaned by other users, which further strengthens his trust in the system. He generally no longer has to worry about a dirty shared scooter or car — although CleanRide cannot guarantee a 100% perfectly clean vehicle; nothing is ever completely foolproof. After all, technically, a bird could still poop on the seat or handlebars in the meantime. Still, he feels satisfied with the ride and the ease of using CleanRide, and he tells his friends about his positive experience with the service, recommending it to them!

Conclusion

By using CleanRide, users experience not only a more hygienic, but also a more reliable and pleasant user journey. The system encourages everyone to contribute to keeping the vehicles clean, leading to a better and healthier environment for all users.

Hand-drawn storyboard of the CleanRide service, featuring the same six scenes:

Wireframing & Prototyping

First Lo-Fi sketches

When developing the CleanRide concept, I began (as shown in the image next to this/above) by creating low‑fidelity (Lo‑Fi) sketches to visually capture my ideas and explore how the app’s interface and features could take shape. These sketches served as the first step in the prototyping process, focusing on quickly and easily testing different design elements without the constraints of detailed, visually polished designs.

The Lo‑Fi sketches helped me structure the user experience and test various app features, such as:

- Interactive Map: Allows users to find the nearest scooter or hub and view the real‑time cleaning status of the vehicles.

- Hygiene‑kit integration (and restocking): Sketches showing how users are informed about the presence and use of the hygiene kit in the vehicle.

- Feedback system: A simple system that lets users assess and report the hygiene condition of a vehicle after use.

- Reward system: Visual concepts for rewarding users who contribute to keeping the vehicles clean.

These early sketches were crucial for identifying potential pain points and gathering feedback from prospective users and stakeholders. They provided insight into which features were essential and which needed further refinement. The Lo‑Fi sketches served as a cost‑effective way to validate ideas and lay the foundation for more detailed designs and, ultimately, a functional (Hi-Fi) prototype.

Hi-Fi Prototype — Version 1

Test rounds

Test plan

Scenario:

Imagine you’re a young man or woman (around 21 years old) who needs to go to a posh (fancy, high-class) party on a Saturday evening. You don’t own a car, but you do have a driver’s license — and for some reason, public transport isn’t running. Fortunately, there’s a shared‑mobility hub nearby where you can reserve a shared scooter. However, you’re a bit of a germaphobe, so good hygiene is very important to you — especially tonight, because you want to look good at the party, and smell good too.

Task 1: Imagine you’ve already downloaded the app on the recommendation of one of your friends, so you already have a CleanRide account — but you've barely used the app. Now that public transport isn’t running, you’re going to try shared mobility for the first time. You specifically want to use a shared scooter, because there’s a shared‑mobility hub near your home with several shared scooters available.

Task 2: Imagine you arrive at the hub and notice that your vehicle is actually quite dirty, even though the app says it should be clean. How do you report this? And what will you do next?

Task 3: So, your shared vehicle is dirty, even though the app says the previous user cleaned it. This isn’t correct, so give the previous user a negative review (0 or 1 star).

Task 4: Since you’re already using the app and you’re not in a hurry, you’re now curious how many Reward points you’ve collected so far. How can you check your Reward balance (the number of Reward points)?

Task 5: Imagine you want to quickly spray your helmet with some deodorizing (and sanitizing) spray because it smells like sweat — and of course you don’t want to smell sweaty at the party — but you discover that the spray bottle in the hygiene kit is empty… What do you do now?

Test results and feedback

Round 1: Bruno (19 years old, colleague)

Task 1:

It went well — the concept is clear, although the visual design could perhaps be a bit more appealing or more in line with an existing app. I let the test user (Bruno) explore the app freely for a moment, and he navigated through it on his own.

Task 2:

He indicates here that the vehicle is dirty, and he also notices that you can rate the vehicle’s smell. He thinks it’s nice that the smell rating uses a rotary knob/switch — very original.

Task 3:

This feature was not yet available in the tested app/prototype on the day of testing.

Task 4:

He clicked on the menu in the top left and immediately found it under ‘My Account’.

Task 5:

The test person (Bruno) sees in the app that there should be a hygiene kit somewhere in this scooter, which is supposed to contain a deodorizing (and sanitizing) spray, but the spray is empty. At this moment, it wasn’t clear to him what else he was supposed to do — this could be made clearer.

Round 2: Sten (26 years old, external participant)

Task 1:

It went well — the concept is clear. For a first‑time user, the instructions are clear so far. I let the test user (Sten) explore the app freely for a moment, and he navigated through it on his own.

Task 2:

Quote from the test user Sten: "In the app/onboarding, you are immediately asked about the vehicle’s hygiene status. Here, I can indicate that it’s dirty and doesn’t smell good. I assume this is registered in the system?"

Task 3:

This isn’t fully clear in the app yet; according to the test participant, it’s still not clear where you can give the previous user a (negative) review.

Task 4:

Quote from the test user Sten: "You go to your profile, and that’s where you should see the points you’ve collected. That’s correct."

Task 5:

Quote from the test user Sten: "No choice? Or just use a wet wipe and go to the party with a clean hairnet. What else can I do?”

At this point, it is still quite unclear to the user that the larger hubs also have so‑called ‘Cleaning Stations’, where you can use a QR code to pick up or refill new supplies of wet wipes or your deodorizing (and sanitizing) spray bottle. (This was an improvement point in the app that I still needed to work out.)

Round 3: Jan (24 years old, external participant)

Task 1:

Test user Jan found the app intuitive and user‑friendly. He was able to reserve a shared scooter without any problems, and he appreciated that the app guided him step by step through the onboarding process.

Task 2:

Jan is now disappointed that the scooter he reserved is dirty. He uses the app to report the hygiene status and expected this to be resolved quickly. But how this actually works is still not entirely clear — quote from the test user Jan: "How do you do that?"

Task 3:

Jan had trouble finding the option to leave a review. He suggested that the app should include a clearer indication or button for giving feedback about the previous user.

Task 4:

Jan was able to locate his Reward balance in his profile without difficulty. He was pleased to see how many points he had already accumulated and found this feature motivating.

Task 5:

Jan was not aware of the ‘Cleaning Stations’ and used a wet wipe from the hygiene kit instead. He noted that it would be helpful if the app provided information about the availability of cleaning stations at the hubs, as well as which hubs offer them (on a map for example).

So, Jan indicated that the app generally worked well, but that there is still room for improvement in certain areas, such as the communication around cleaning procedures and providing/giving feedback on vehicle hygiene. He also suggested informing users more clearly about the ‘Cleaning Stations’ at certain (bigger) hubs, and offering the option to leave a review immediately after using the shared vehicle.

Round 4: Shiga (26 years old, external participant)

Task 1:

Test user Shiga successfully reserves a shared scooter through the app.

Task 2:

Shiga reports the issue by switching to another shared scooter in the app, using the designated button for this action.

Task 3:

Shiga reports in the app that the previous user left the scooter in an unclean (dirty) state, which likely results in penalty points for that user’s CleanRide balance. However, she mentioned that the points system feels unclear and questioned how it actually works.

Task 4:

Shiga navigates to ‘My Account’ via the app’s menu (hamburger menu) to view her points balance, which she was able to do quickly and without difficulty.

Task 5:

Shiga attempts to contact customer support through the app, first using the AI chat(bot) and then proceeding through the onboarding flow to report the empty spray bottle. However, she is unsure whether any Cleaning Stations are available near her current location. This information could potentially be displayed on the map as well.

Shiga did mention that additional explanation about the Cleaning Stations would be helpful — specifically where they are located and what they look like.

Round 5: Richie (25 years old, external participant)

Task 1:

Test user Richie opens the CleanRide app and searches for the nearest available shared scooter. He uses the interactive map to identify the closest shared mobility hub.

He selects a scooter marked as ‘clean’ and reserves it for the evening.

Task 2:

Richie arrives at the hub and notices that the scooter is dirty. He uses the onboarding section of the app to report the issue.

He chooses to reserve another scooter that is clean (by switching scooters in the app), or he uses the Cleaning Station available at the same hub to clean the scooter himself.

Task 3:

Richie leaves a negative review for the previous user through the app’s review feature, selecting 0 or 1 star and uploading the required evidence (a photo). He noted that the layout of this screen feels somewhat crowded or visually compressed. This is clearly an area for improvement on my part as the UX Designer for this case/project.

Task 4:

Richie navigates to the ‘My Account’ section of the app to view his Reward points balance.

He finds an overview of the points he has accumulated, along with any rewards he is eligible to claim.

Task 5:

Richie reports the empty deodorizing (and sanitizing) spray bottle through the app’s ‘Report Issue’ feature.

He requests a replacement or looks for an alternative solution, possibly checking whether a Cleaning Station is available nearby on the map.

Final version Hi-Fi Prototype CleanRide (in the style of Felyx)

The validation of the concept through user trips and interviews (which are detailed in the accompanying case study (or 'Productbiografie' in Dutch)) confirms that the proposed solutions align with user needs.

My final recommendation/advise to Vervoerregio Amsterdam (VRA) is to invest in the further development and implementation of this CleanRide concept, given its potential to significantly improve the usability and hygiene of shared‑mobility services.

My final recommendation/advise to Vervoerregio Amsterdam (VRA) is to invest in the further development and implementation of this CleanRide concept, given its potential to significantly improve the usability and hygiene of shared‑mobility services.

Conclusion

This project, carried out within the Service Design minor, has provided in‑depth insight into the challenges and opportunities of shared mobility in the Amsterdam region. Through extensive research — including interviews, user trips, user journeys, and desk research — the focus was placed on improving hygiene within shared‑mobility services and optimizing mobility hubs.

The solutions developed, such as the CleanRide app extension for existing shared‑mobility providers and the hygiene kits, demonstrate a strong commitment to user comfort and convenience. The project highlights the need for innovation and collaboration between stakeholders to achieve a sustainable and accessible mobility future. With the feedback from Vervoerregio Amsterdam and the ongoing design iterations, this project represents a meaningful step toward creating an inclusive and hygienic shared‑mobility experience for all users.

Personal reflection

On a personal and professional level, this project has not only strengthened my skills in both UX/UI and Service Design, but also deepened my understanding of the challenges and opportunities within the shared mobility sector. CleanRide reflects a strong commitment to improving the user experience and contributing to cleaner, more accessible urban and suburban mobility.

In this project, I learned a great deal about UX/UI Design (and UX Research) as well as Service Design, with a strong focus on methods and techniques essential for creating user‑centered solutions. By developing a need‑based profile, I was able to better understand and address the specific needs and behaviors of my target audience. The service blueprint helped map the entire user journey and identify potential pain points, allowing me to resolve them effectively.

In addition, throughout the process I gained valuable insights into content operations, examining which content was already available, applying the RACI model, and exploring the differences between static design and dynamic content. Creative research methods helped me generate and validate innovative (and out-of-the-box) solutions through extensive user interviews and user trips.

These experiences and insights have not only helped me develop a valuable, intuitive, and user‑centered concept, but have also provided me with a solid foundation in Service and UX/UI Design that I can apply in future projects.